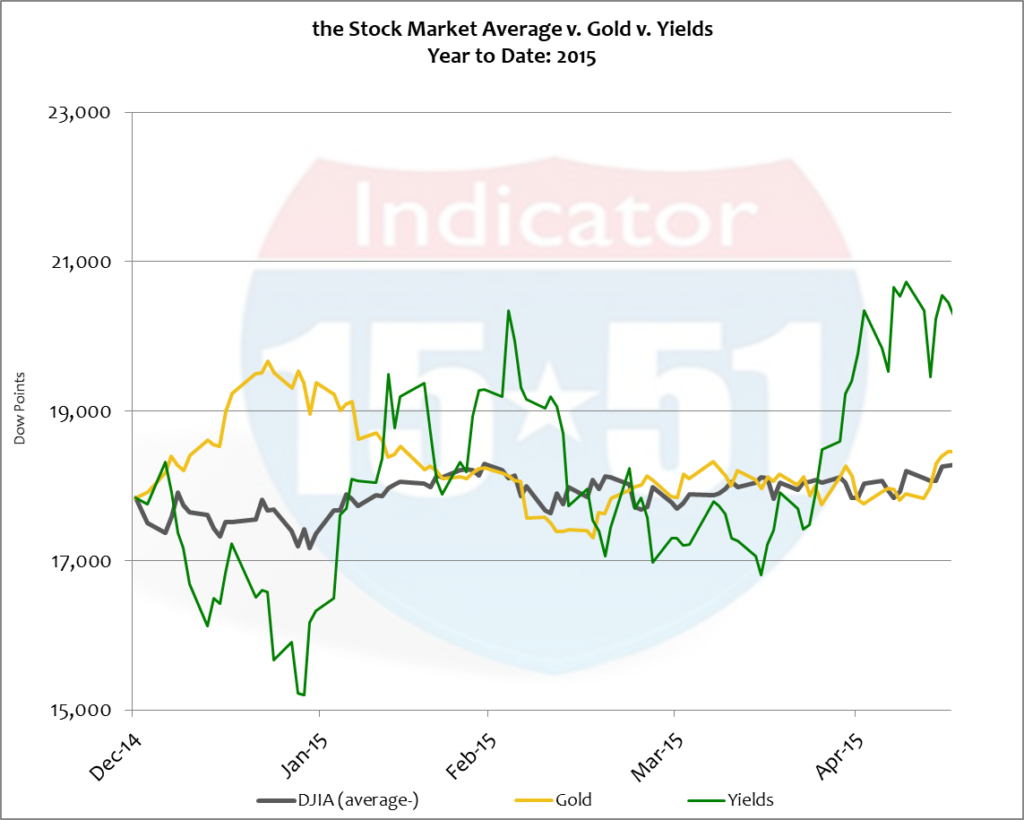

There is a lot of confusion surrounding the bond market and yields, and there is one misnomer I feel compelled to address. A recent Wall Street Journal article entitled, U.S. Government Bonds Rise; Foreign Investors Pile into Auctions (May 14, 2015) highlights a common misconception about bonds. The author attempts to explain the recent pop in yields by citing strong demand for a recent 10 Year auction. They’re up 28% since their January low. See below.

But strong demand doesn’t cause yields to rise – it causes them to fall. Recall that quantitative easing (QE) created new and additional bond demand in order to keep yields low – which it did. If the premise that strong demand causes yields to rise were true, QE would have raised yields not lowered them.

Bond values fall when yields rise.

The article’s author opines, “Many investors see the [bond] selloff as a correction…They don’t expect bond yields to rise sharply given the tepid economic growth outlook …” To qualify his stance the author quotes a senior portfolio manager at Invesco Ltd. who said, “We still believe there are structural headwinds to the global economy,” then the author adds, “which would contain a rise in bond yields.”—And that’s the great misnomer.

To believe that yields are tied directly to economic performance – that is, weak economies produce low yields – is complete and utter foolishness. Take Greece for example; their economy is weak, and in fact, is in recession. Low yields are extremely helpful during recessions – yet their 1o year yield is 10.5% and their two year yield is 21%. An inverted yield curve is when short term yields are higher than long term yields. That’s where Greece is today – it’s inverted – despite their economy experiencing “structural headwinds.”

Instead, yields are tied directly to the associated risk of default. Greece can’t afford itself and there is little doubt that they will fink on a substantial portion of their debts – the only question is when. That’s why short term lenders are demanding more than 20% interest to lend them money. They’re weak and risk of default is high, and so are their yields. In their case, a stronger economy would lower yields, as their risk of default would lessen. Not the other way around.

To invest in bonds right now is a risky proposition at the very least. To chase higher yields from borrowers like Greece is a fool’s game – and so not worth the associated risks. And at just a couple of bips above inflation, a 2% U.S. bond is just as risky. Sure American yields can dip down lower. Heck, Germany’s 10 year yield is around .67%. Indeed, bets can be placed on lower near term yields and perhaps money can be made. But that doesn’t mean the odds favor such a position.

In fact, the opposite is true. The odds for bonds are in the house’s favor because there is more room for yields to move up than down. To put it another way, there’s more room for bond values to fall rather than rise because yields remain at historic lows. In markets such as these, investors don’t buy U.S. bonds to make money. They buy them for safety and security. They buy them to not lose everything should the world fall apart.

That’s why foreign money is flooding into U.S. bonds. The United States has the greatest system of government, the strongest middle class on the planet, and is the only country to never fink on a loan obligation. And even though the U.S. is more than 100% leveraged (that is, there is more debt than economic output) risk of default is nil. For that reason U.S. yields will remain low as long as the Federal Reserve wants them low, and inflationary pressure remains mute. The level of economic output has little to do with it. After all, yields have been low in America since the Great Recession.

It’s a different story around the world. Countries like Greece are having a hard time raising money even though they offer high interest rates. But let’s face it, twenty percent interest payments aren’t worth a hill of beans if the checks don’t clear. Greece needs a stronger economy, not a weaker one, to attract capital at lower rates.

Indeed, economic strength would prompt central bankers to raise interest rates. Such a move would be in hopes to slow growth and thwart inflation. But that’s much different from the Wall Street Journal’s pronouncement, that a sluggish global economy will contain high yields. The only thing a sluggish economy contains is prosperity.

Just ask the Greeks.

Stay tuned…